During the Albigensian Crusade, the Templars ostensibly remained neutral, confining themselves to the role of witnesses. At the same time, however, the Grand Master at the time would seem to have made the Order’s position clear when he declared there was in fact only one true Crusade the Crusade against the Saracens. Moreover, a careful examination of contemporary accounts reveals that the Templars provided a haven for Many Cathar refugees.”? On occasion they do seem to have taken up arms on these refugees’ behalf. And an inspection of the Order’s rolls towards the beginning of the Albigensian Crusade reveals a major influx of

During the Albigensian Crusade, the Templars ostensibly remained neutral, confining themselves to the role of witnesses. At the same time, however, the Grand Master at the time would seem to have made the Order’s position clear when he declared there was in fact only one true Crusade the Crusade against the Saracens. Moreover, a careful examination of contemporary accounts reveals that the Templars provided a haven for Many Cathar refugees.”? On occasion they do seem to have taken up arms on these refugees’ behalf. And an inspection of the Order’s rolls towards the beginning of the Albigensian Crusade reveals a major influx of Cathars into the Temple’s ranks where not even Simon de Montfort’s crusaders would dare to challenge them. Indeed, the Templar rolls of the period show that a significant proportion of the Order’s high-ranking dignitaries were from Cathar families. 14 In the Languedoc Temple officials were more Frequently Cathar than Catholic. What is more, the Cathar nobles who enrolled in the Temple do not appear to have moved about the world as much as their Catholic brethren. On the contrary, they appear to have remained for the most part in the Languedoc, thus creating for the Order a long-standing and stable base in the region.

By virtue of their contact with Islamic and Judaic cultures, the Templars had already absorbed a great many ideas alien to orthodox Roman Christianity. Templar Masters, for example, often employed Arab secretaries, and many Templars, having learnt Arabic in captivity, were fluent in the language. A close rapport was also maintained with Jewish communities, financial interests and scholarship. The Templars had thus been exposed to many things Rome would not ordinarily countenance.Through the influx of Cathar recruits, they were now exposed to Gnostic dualism as well if, indeed, they had ever really been strangers to it.

Philippe first had to enlist the co-operation of the pope, to whom, in theory at any rate, the Templars owed allegiance and obedience. Between 1303 and 1305, the French king and his ministers engineered the kidnapping and death of one pope (Boniface VIII) and quite possibly the murder by poison of another (Benedict XI). Then, in 1305, Philippe managed to secure the election of his own candidate, the archbishop of Bordeaux, to the vacant papal throne. The new pontiff took the name Clement V. Indebted as he was to Philippe’s influence, he could hardly refuse the king’s demands. And these demands included the eventual suppression of the knights Templar.

Philippe planned his moves carefully. A list of charges was compiled, partly from the king’s spies who had infiltrated the Order, partly from the voluntary confession of an alleged renegade Templar. Armed with these accusations, Philippe could at last move; and when he delivered his blow, it was sudden, swift, efficient and lethal. In a security operation worthy of the SS or Gestapo, the king issued sealed and secret orders to his seneschals throughout the country. These orders were to be opened everywhere simultaneously and implemented at once. At dawn on Friday, October 13th, 1307, all Templars in France were to be seized and placed under arrest by the king’s men, their preceptories placed under royal sequestration, their goods confiscated. But although Philippe’s objective of surprise might seem to have been achieved, his primary interest the Order’s immense wealth eluded him. It was never found, and what became of the fabulous ‘treasure of the Templars’ has remained a mystery.

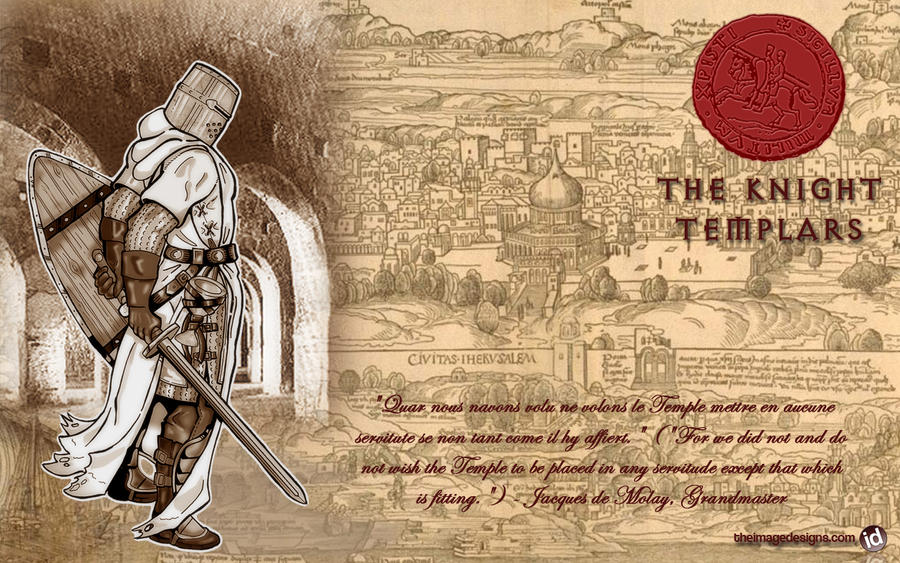

In fact it is doubtful whether Philippe’s surprise attack on the Order was as unexpected as he, or subsequent historians, believed. There is considerable evidence to suggest the Templars received some kind of advance warning. Shortly before the arrests, for example, the Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, called in many of the Order’s books and extant rules, and had them burnt. A knight who withdrew from the Order at this time was told by the treasurer that he was extremely ‘wise’, as catastrophe was imminent. An official note was circulated to all French preceptories, stressing that no information regarding the Order’s customs and rituals was to be released.

In any case, whether the Templars were warned in advance or whether they deduced what was in the wind, certain precautions were definitely taken.In the first place the knights who were captured seem to have submitted passively, as if under instructions to do so. At no point is there any record of the Order in France actively resisting the king’s seneschals. In the second place there is persuasive evidence of some sort of organised flight by a particular group of knights virtually all of whom were in some way connected with the Order’s Treasurer. It is not perhaps surprising, therefore, that the treasure of the Temple, together with almost all its documents and records, should have disappeared. Persistent but unsubstantiated rumours speak of the treasure being smuggled by night from the Paris preceptory, shortly before the arrests. According to these rumours, it was transported by wagons to the coast presumably to the Order’s naval base at La Rochelle and loaded into eighteen galleys, which were never heard of again. Whether this is true or not, it would seem that the Templars’ fleet escaped the king’s clutches because there is no report of any of the Order’s ships being taken. On the contrary, those ships appear to have vanished totally, along with whatever they might have been carrying.

In France, at least, the fate of the arrested Templars was effectively sealed. Philippe harried them savagely and mercilessly. Many were burned, many more imprisoned and tortured. At the same time the king continued to bully the pope, demanding ever more stringent measures against the Order. After resisting for a time, the pope gave way in 1312, and the Knights Templar were officially dissolved without a conclusive verdict of guilt or innocence ever being pronounced. But in Philippe’s domains, the trials, inquiries and investigations continued for another two years. At last, in March 1314, Jacques de Molay, the Grand Master, and Geoffroi de Charnay, Preceptor of Normandy, were roasted to death over a slow fire. With their execution, the Templars ostensibly vanish from the stage of history. Nevertheless, the Order did not cease to exist. Given the number of knights who escaped, who remained at large or who were acquitted, it would be surprising if it had.

Philippe had tried to influence his fellow monarchs, hoping thereby to ensure that no Templar, anywhere in Christendom, should be spared. Indeed, the king’s zeal in this respect is almost suspicious. One can perhaps understand him wanting to rid his own domains of the Order’s presence. It is rather less clear why he should have been so intent on exterminating Templars elsewhere. Certainly he himself was no model of virtue; and it is difficult to imagine a monarch who arranged for the deaths of two popes being genuinely distressed by infringements of faith. Did Philippe simply fear vengeance if the Order remained intact outside France? Or was there something else involved?

In any case, his attempt to eliminate Templars outside France was not altogether successful. Philippe’s own sonin-law, for example, Edward II of England, at first rallied to the Order’s defence. Eventually, pressured by both the pope and the French king, he complied with their demands, but only partially and tepidly. Although most Templars in England seem to have escaped completely, a number were arrested. Of these, however, most received only light sentences sometimes no more than a few years’ penance in abbeys and monasteries, where they lived in generally comfortable conditions. Their lands were eventually consigned to the Knights Hospitaller of Saint John, but they themselves were spared the vicious persecution visited upon their brethren in France.

In Lorraine, which was part of Germany at the time, not part of France, The Templars were supported by the duke of the principality. A few were tried and exonerated. Most, it seems, obeyed their Preceptor, who reputedly advised them to shave their beards, don secular garb and assimilate themselves into the local populace.

In Germany proper the Templars openly defied their judges, threatening to take up arms. Intimidated, their judges pronounced them innocent; and when the Order was officially dissolved, many German Templars found a haven in the Hospitallers of Saint John and in the Teutonic Order. In Spain, too, the Templars resisted their persecutors and found a

refuge in other orders.

In Portugal the Order was cleared by an inquiry and simply modified its name, becoming Knights of Christ. Under this title they functioned well into the sixteenth century, devoting themselves to maritime activity. Vasco da Gama was a Knight of Christ, and Prince Henry the Navigator was a Grand Master of the Order. Ships of the Knights of Christ sailed under the familiar red pat tee cross. And it was under the same cross that Christopher Columbus’s three caravels crossed the Atlantic to the New World. Columbus himself was married to the daughter of a former Knight of Christ, and had access to his father-inlaw’s charts and diaries.

Thus, in a number of diverse ways, the Templars survived the attack Of October 13th, 1307. And in 1522 the Templars’ Prussian progeny, the Teutonic Knights, seculari sed themselves, repudiated their allegiance To Rome and threw their support behind an upstart rebel and heretic Named Martin Luther. Two centuries after their dissolution, the Templars, however vicariously, were exacting revenge on the Church which had betrayed them.

THE END

THE HOLY BLOOD AND THE HOLY GRAIL